Inspecting Swift's Observation. Exploring Benefits, Issues and solutions

It was a really long road to Observation, as an engineers and part of the community we have tried and learned a lot of different approaches during these years and finally we are currently at the almost like a perfect solution the core problem of UI apps.

UIKit and Manual State Management

In the early days of iOS development, UIKit was the primary framework used to build user interfaces. State management was a manual and often cumbersome process. Developers had to handle state using instance variables, singletons, or other global objects. This approach, while flexible, had several drawbacks:

- Complexity: Managing state manually often led to complex and error-prone code.

- Scalability: As applications grew, maintaining and debugging state became increasingly difficult.

- Thread Safety: Ensuring thread safety required additional effort, as UIKit was not inherently thread-safe.

Despite these challenges, this approach allowed for a high degree of control and customization, which was appreciated by experienced developers.

Reactive Programming: RxSwift

As applications became more complex, developers found better ways to manage state and asynchronous events. Reactive programming frameworks like RxSwift gained popularity. RxSwift introduced a new paradigm for state management, emphasizing declarative code and reactive streams.

Pros:

- Declarative: Allowed developers to describe how state should change over time in a more readable and maintainable way.

- Composition: Made it easier to compose and transform state streams.

- Asynchronous Handling: Simplified handling of asynchronous events and state changes.

Cons:

- Learning Curve: Steep learning curve for developers unfamiliar with reactive programming concepts.

- Boilerplate: Required a significant amount of boilerplate code to set up and manage observables and subscriptions.

RxSwift was embraced by many for its powerful capabilities in managing complex state and asynchronous operations.

@State and @ObservedObject

The introduction of SwiftUI in 2019, brought a new declarative syntax and a modern approach to state management with @State and @ObservedObject.

- @State: Designed for simple state that is local to a view. It allows developers to declare state variables that SwiftUI manages automatically.

- @ObservedObject: Intended for more complex or shared state that needs to be observed by multiple views. It relies on the

ObservableObjectprotocol and@Publishedproperties to trigger updates.

SwiftUI follows the principle of “single source of truth”. The view tree can only be updated and the body re-evaluated by modifying the state subscribed by the View. In iOS 14, Apple added @StateObject, which complements the scenario of holding reference type instances in the View, making SwiftUI's state management more comprehensive.

But …

When subscribing to reference types, a major issue with ObservableObject, which acts as the model type, is that it can't provide attribute-level subscriptions. In View, the subscription to ObservableObject is based on the entire instance. As long as any @Published property on the ObservableObject changes, it triggers the objectWillChange publisher of the entire instance to emit changes, causing all Views subscribed to this object to re-evaluate. In complex SwiftUI apps, this can lead to serious performance issues and hinder the scalability of the program, thus requiring careful design by the user to avoid large-scale performance degradation.

The lack of granularity in updates

Consider this example

class ProfileViewModel: ObservableObject {

@Published var name: String = ""

@Published var age: Int = 0

@Published var bio: String = ""

}

struct ProfileView: View {

@ObservedObject var viewModel: ProfileViewModel

var body: some View {

VStack {

Text("Name: \(viewModel.name)")

Text("Age: \(viewModel.age)")

// Bio is not used in this view

}

}

}

In this scenario, even if only the bio property changed, the entire ProfileView would be re-evaluated, despite bio not being used in the view. This led to unnecessary computations and potential performance issues, especially in large and complex view hierarchies.

Observation

At WWDC23, Apple introduced a brand-new Observation framework, hoping to solve the confusion and performance degradation issues related to state management in SwiftUI. The way this framework works seems magical, as you can achieve attribute-level subscriptions in the View without any special syntax or declarations, thereby avoiding any unnecessary refreshes. Today, we'll take a closer look at the story behind it.

This article will help you:

- Understand what exactly the Observation framework does, and how it accomplishes it.

- Understand the benefits it brings to us compared to previous solutions.

- Understand some of the trade-offs we make when dealing with SwiftUI state management today.

- Why it is only used with classes? Can we use Observation for value types?

- What about Observation in iOS 13 ?

How the Observation framework works

Incorporating Observation into your project is quite simple. Just add the @Observable attribute before your model class declaration. This allows you to seamlessly integrate it into your View. Any changes to the stored or computed properties of the model instance will automatically trigger a re-evaluation of the View's body, ensuring that your View always reflects the current state of the model.

import SwiftUI

import Observation

@Observable final class HomeTask {

var title: String

var isCompleted: Bool

init(title: String, isCompleted: Bool) {

self.title = title

self.isCompleted = isCompleted

}

}

var homeTask = HomeTask(title: "Complete SwiftUI project", isCompleted: false)

struct ContentView: View {

var body: some View {

let _ = Self._printChanges()

VStack {

HStack {

Image(systemName: homeTask.isCompleted ? "checkmark.circle.fill" : "circle")

Text(homeTask.title)

.strikethrough(homeTask.isCompleted)

.foregroundColor(homeTask.isCompleted ? .gray : .black)

}

.padding()

Button("Mark as Completed") {

homeTask.isCompleted = true

}

.padding()

}

}

}

At first glance, this seems a bit magical: we didn’t declare any relationship between homeTask and ContentView. Simply by accessing isCompleted in View.body, we have completed the subscription. The specific use of @Observable in SwiftUI and the migration from ObservableObject to @Observable are fully explained in the WWDC Discover Observation in SwiftUI session. Here, I will focus things what is happening behind the hood . If you haven't watched the related video yet, I highly recommend that you do so first.

Now lets check if the problem of ObservedObject is solved here, before diving deeply. Let’s add domain based property in our state which we will not use inside the View, and lets mutate it.

Remember: In the context of ObservableObject if any property of the state would change, it will emmit View to redraw, lets check what will happen in the case of Observable.

@Observable final class HomeTask {

var title: String

var isCompleted: Bool

var priority: Int = 0

init(title: String, isCompleted: Bool) {

self.title = title

self.isCompleted = isCompleted

}

}

Lets add priority for our tasks, and add possibility to mutate it from the View

struct ContentView: View {

var body: some View {

let _ = Self._printChanges()

VStack {

HStack {

Image(systemName: homeTask.isCompleted ? "checkmark.circle.fill" : "circle")

Text(homeTask.title)

.strikethrough(homeTask.isCompleted)

.foregroundColor(homeTask.isCompleted ? .green : .white)

}

.padding()

Button("Mark as Completed") {

homeTask.isCompleted = true

}

.padding()

Button("Increase Priority") {

homeTask.priority = homeTask.priority + 1

}

.padding()

}

}

}

And lets check how it is working in practice.

You can see the mutation for isCompletedproperty makes View to redraw but it is not doing same for priority property, cause priority is not used anywhere inside the View, and View is not rendering any data from priority to the View, but it actually mutates it.

Its magic, isn’t it ? Just adding one single Macroon our model fixed the most complex and as well straightforward problem of the SwiftUI Observability.

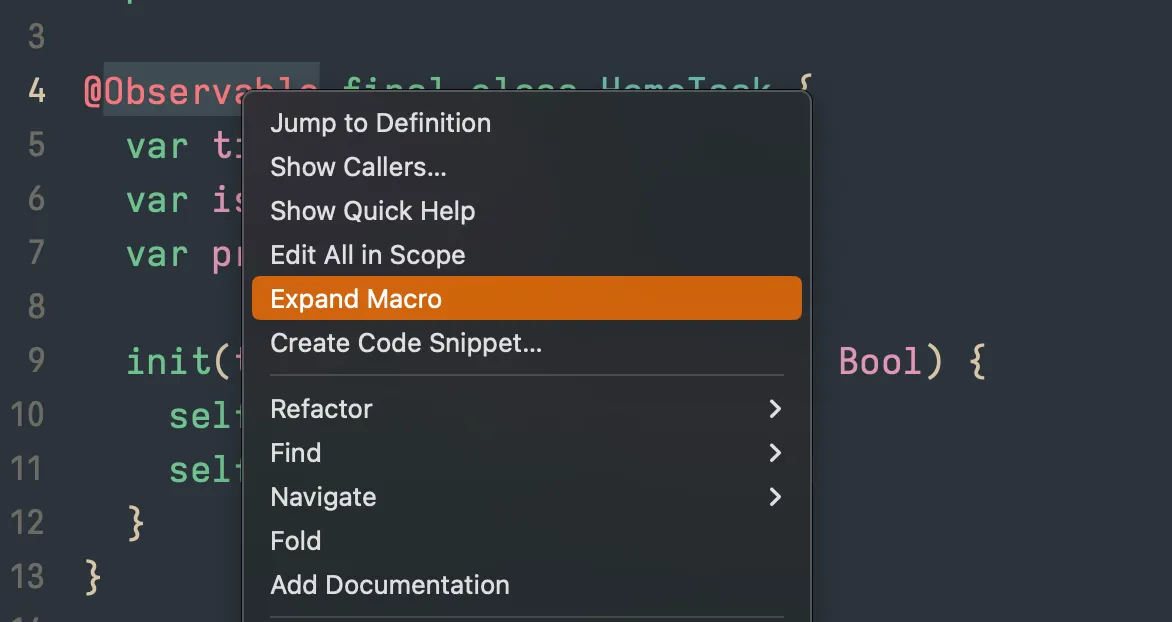

Macro? Yes @Observable is Macro, it looks like a property-wrapper but not its whole new feature. They were introduced in Swift 5.9 as a powerful metaprogramming feature. Swift macros allow developers to generate or transform code at compile time. You can watch about macros to WWDC: Write a Swift Macros

The Observable macro and its expansion

One of the coolest feature of Macros is to expand it in realtime, to check actually what code it adds into your context.

final class HomeTask {

@ObservationTracked

var title: String

@ObservationTracked

var isCompleted: Bool

@ObservationTracked

var priority: Int = 0

init(title: String, isCompleted: Bool) {

self.title = title

self.isCompleted = isCompleted

}

@ObservationIgnored private let _$observationRegistrar = Observation.ObservationRegistrar()

internal nonisolated func access<Member>(

keyPath: KeyPath<HomeTask , Member>

) {

_$observationRegistrar.access(self, keyPath: keyPath)

}

internal nonisolated func withMutation<Member, MutationResult>(

keyPath: KeyPath<HomeTask , Member>,

_ mutation: () throws -> MutationResult

) rethrows -> MutationResult {

try _$observationRegistrar.withMutation(of: self, keyPath: keyPath, mutation)

}

}

extension HomeTask: Observation.Observable {

}

Here is the code which Observable macro generates, lets deep dive into it and check what is happening here.

- It adds

@ObservationTrackedto all stored properties.@ObservationTrackedis also a macro that can be expanded further. We'll see later that this macro converts the original stored properties into computed properties. Additionally, for each converted stored property, the@Observablemacro adds a new stored property with an underscore prefix but with another macro on of them@ObservationIgnored - It adds content related to

ObservationRegistrar, including an_$observationRegistrarinstance, as well as two helper methods,accessandwithMutation. These two methods acceptKeyPathofHomeTaskand forward this information to the relevant methods of the registrar. - It makes

HomeTaskconform to theObservation.Observableprotocol. This protocol doesn't require any methods, it only serves as a compilation aid.

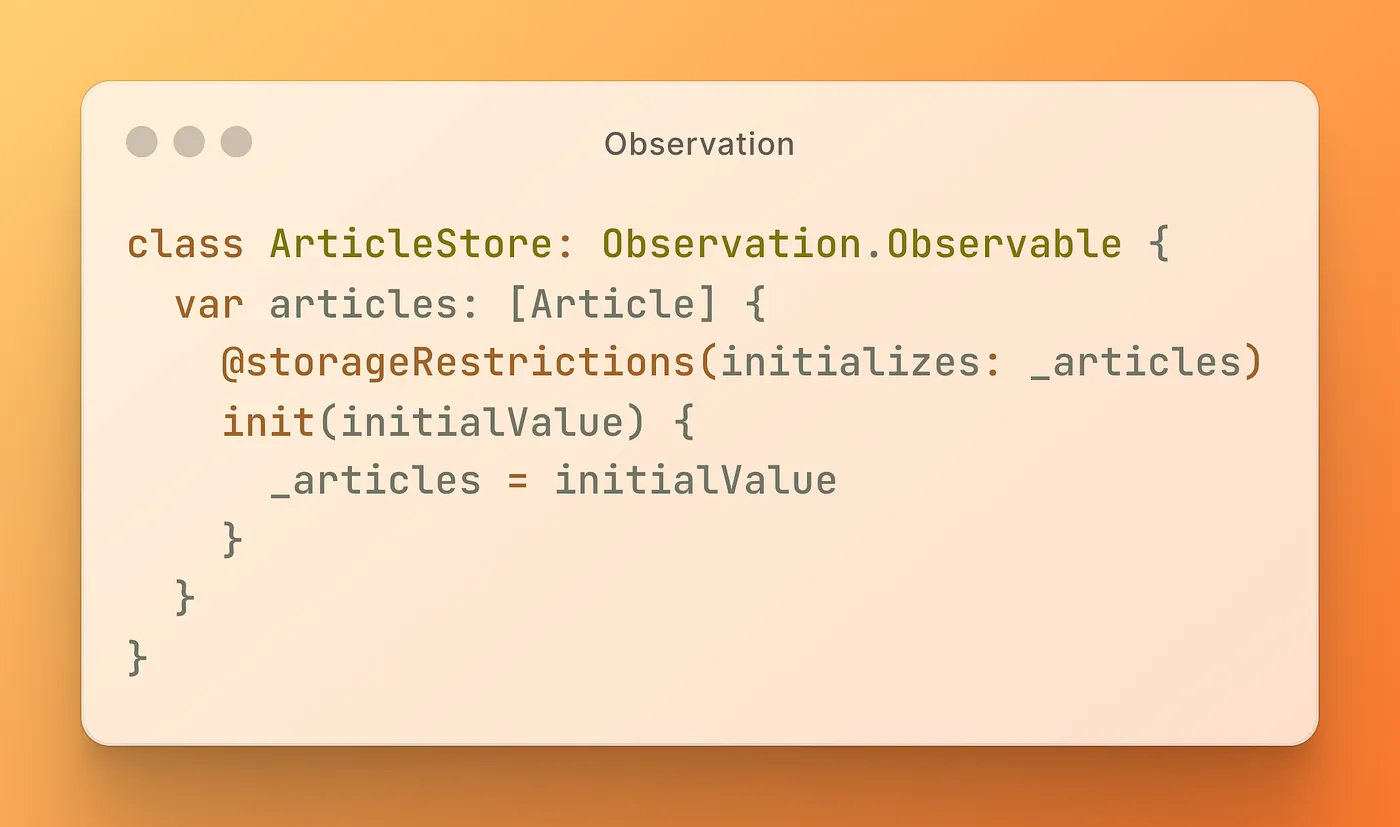

Lets also expand @ObservationTracked macro on a title

var title: String {

@storageRestrictions(initializes: _title)

init(initialValue) {

_title = initialValue

}

get {

access(keyPath: \.title)

return _title

}

set {

withMutation(keyPath: \.title) {

_title = newValue

}

}

}

Hmm, it becomes interesting. Now lets just copy/paste whole generated code and then we would remove Macro on top of our model and we will just have generated code, which will work as goos as before.

So here is full magic of our Observable Macro.

final class HomeTask {

var title: String {

@storageRestrictions(initializes: _title)

init(initialValue) {

_title = initialValue

}

get {

access(keyPath: \.title)

return _title

}

set {

withMutation(keyPath: \.title) {

_title = newValue

}

}

}

var isCompleted: Bool {

@storageRestrictions(initializes: _isCompleted)

init(initialValue) {

_isCompleted = initialValue

}

get {

access(keyPath: \.isCompleted)

return _isCompleted

}

set {

withMutation(keyPath: \.isCompleted) {

_isCompleted = newValue

}

}

}

var priority: Int = 0 {

@storageRestrictions(initializes: _priority)

init(initialValue) {

_priority = initialValue

}

get {

access(keyPath: \.priority)

return _priority

}

set {

withMutation(keyPath: \.priority) {

_priority = newValue

}

}

}

init(title: String, isCompleted: Bool) {

self.title = title

self.isCompleted = isCompleted

}

@ObservationIgnored private let _$observationRegistrar = Observation.ObservationRegistrar()

@ObservationIgnored private var _title: String

@ObservationIgnored private var _isCompleted: Bool

@ObservationIgnored private var _priority: Int

internal nonisolated func access<Member>(

keyPath: KeyPath<HomeTask , Member>

) {

_$observationRegistrar.access(self, keyPath: keyPath)

}

internal nonisolated func withMutation<Member, MutationResult>(

keyPath: KeyPath<HomeTask , Member>,

_ mutation: () throws -> MutationResult

) rethrows -> MutationResult {

try _$observationRegistrar.withMutation(of: self, keyPath: keyPath, mutation)

}

}

extension HomeTask: Observation.Observable {

}

So what we see here?

init(initialValue)is a new syntax specifically added in Swift 5.9, known as Init Accessors. Since the macro can't rewrite the implementation of the existingHomeTaskinitializer, it provides a "backdoor" for accessing computed properties inHomeTask.init, allowing us to call this init declaration in the computed properties to initialize the newly generated underlying stored property_title.@ObservationTrackedconvertstitleinto a computed property, adding a getter and setter for it. By calling the previously addedaccessandwithMutation, it associates property read-write operations with the registrar.

Rough idea of how the Observation framework works in Swift is like that :

When accessing properties on an instance through a getter in View's body, the observation registrar will leave an "access record" for it and register a method that can refresh the View it resides in, when modifying this value through the setter, the registrar retrieves the corresponding method from the record and call it to trigger a refresh.

ObservationRegistrar and withObservationTracking

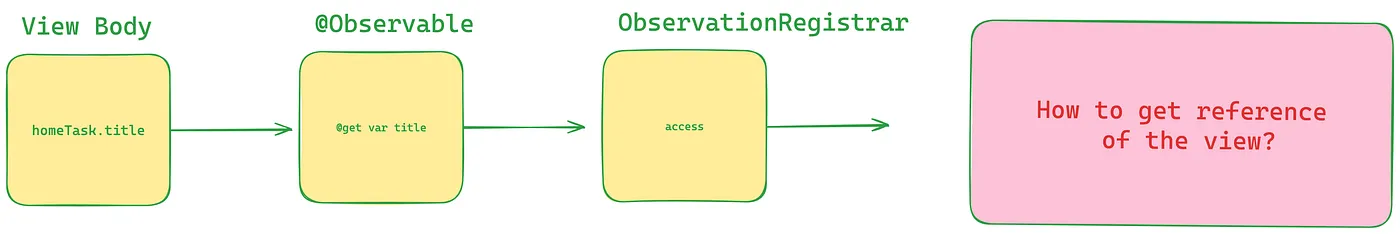

You may have noticed that the access method in ObservationRegistrar has the following signature:

func access<Subject, Member>(

_ subject: Subject,

keyPath: KeyPath<Subject, Member>

) where Subject : Observable

In this method, we can get the instance of the model type itself and the KeyPath involved in the access. However, relying solely on this, we can't get any information about the caller (in other words, the View). There must be something hidden in between.

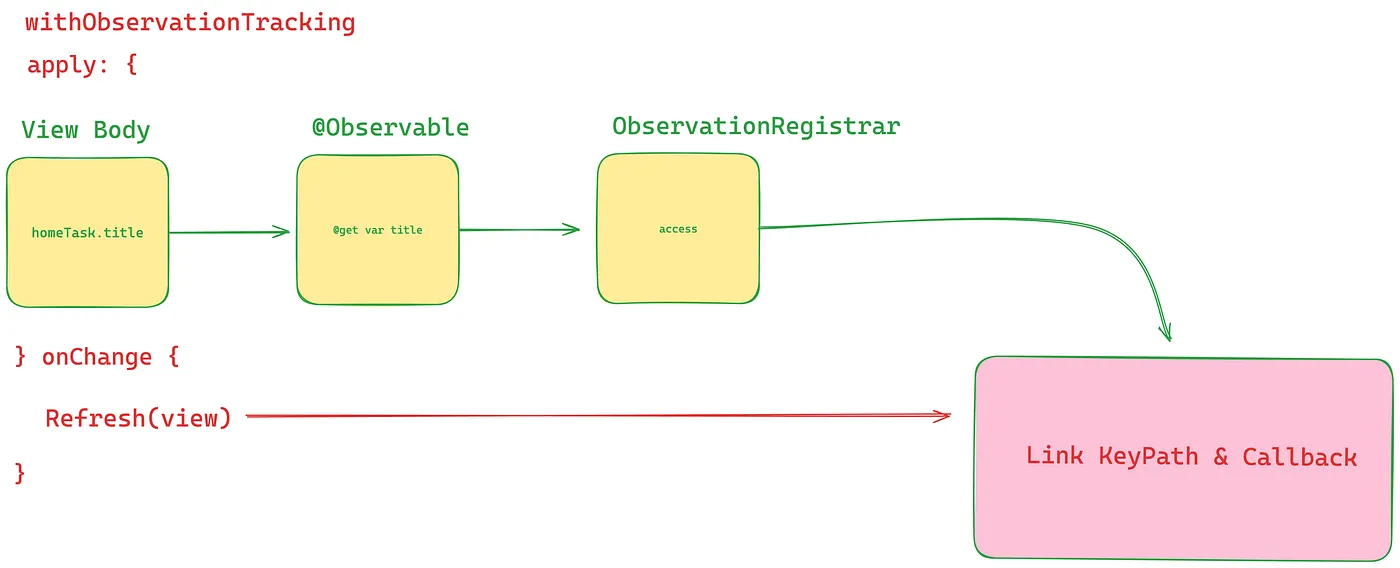

The key is a global function in the Observation framework, withObservationTracking

func withObservationTracking<T>(

_ apply: () -> T,

onChange: @autoclosure () -> () -> Void

) -> T

It takes two closures: in the first apply closure, any variables of the Observable instances accessed will be observed, any changes to these properties will trigger the _onChange_ closure once and only once.

For example, “On Changed” is only printed when isCompleted is changed for the first time.

In the above example, there are a few points worth noting:

- Since in

apply, we only accessed theisCompletedproperty,onChangewasn't triggered when settinghomeTask.title. This property wasn't added to the access tracking. - When we set

homeTask.isCompleted = true,onChangewas called. However, theisCompletedobtained at this time is stillfalse.onChangeoccurs duringwillSetof the property. In other words, we can't get the new value in this closure. - Changing the value of

isCompletedagain won't triggeronChangeagain. The related observations were removed the first time it was triggered.

withObservationTracking plays an important bridging role, linking the observation of model properties in SwiftUI's View.body

Considering the fact that the observation is triggered only once, assuming there’s a renderUI method in SwiftUI to re-evaluate body, we can simplify the entire process as a recursive call:

var homeTask: HomeTask

func renderUI() -> some View {

withObservationTracking {

VStack {

Image(systemName: homeTask.isCompleted ? "checkmark.circle.fill" : "circle")

Button("Complete") {

homeTask.isCompleted = true

}

}

} onChange: {

DispatchQueue.main.async { self.renderUI() }

}

}

Of course, in reality, within onChange, SwiftUI only marks the involved views as dirty and then redraws them in the next main runloop. I've simplified this process here only for demonstration purposes.

Implementation details

Apart from the SwiftUI-related parts, the good news is we don’t have to guess about the implementation of the Observation framework. It’s open-sourced as part of the Swift project. You can find all the source code for the framework here. The framework’s implementation is very concise, direct, and clever. Although it’s very similar to our assumptions overall, there are some details worth noting in the specific implementation.

Tracking access

As a global function, withObservationTracking provides a general apply closure without any type information (it has a type () -> T). The global function itself doesn't have a reference to a specific registrar. So, to associate onChange with the registrar, it must rely on a global variable (the only storage space that a global function can access) to temporarily save the association between the registrar (or key path) and the onChange closure.

In the implementation of the Observation framework, this is achieved by using a custom _ThreadLocal struct and storing the access list in the thread storage behind it. Multiple different withObservationTracking calls can track properties on multiple different Observable objects, corresponding to multiple registrars. And all tracking will use the same access list. You can imagine it as a global dictionary, with the ObjectIdentifier of the model object as the key, and the value contains the registrar and accessed KeyPaths on this object. Through this, we can finally find the contents of the onChange that we want to execute:

struct _AccessList {

internal var entries = [ObjectIdentifier : Entry]()

// ...

}

struct Entry {

let context: ObservationRegistrar.Context

var properties: Set<AnyKeyPath>

// ...

}

struct ObservationRegistrar {

internal struct Context {

var lookups = [AnyKeyPath : Set<Int>]()

var observations = [Int : () -> () /* content of onChange */ ]()

// ...

}

}

Thread safety

When establishing an observation relationship (in other words, calling withObservationTracking), the internal implementation of the Observation framework uses a mutex to ensure thread safety. This means that we can use withObservationTracking safely on any thread without worrying about data race issues.

During the triggering of observations (the setter side), no additional thread handling is performed for the invocation of observations. The onChange will be executed on the thread where the first observed property is set. This means that if we want to carry out some thread-safe operations within onChange, we need to be aware of the thread on which the call is taking place.

In SwiftUI, this isn’t a problem, as the re-evaluation of View.body will be "consolidated" and performed on the main thread. However, if we're using withObservationTracking separately outside of SwiftUI and want to refresh the UI within onChange, it's best to perform a check about the current thread.

Performance tips

Compared to the traditional ObservableObject model type that observes the entire instance, using @Observable for property-level observation can naturally reduce the number of times View.body is re-evaluated (because accessing properties on an instance will always be a subset of accessing the instance itself). In @Observable, a simple access to an instance does not trigger re-evaluation, so some former performance "optimization tricks", such as trying to split the View's model into fine-grained parts, may no longer be the best solution.

For instance, when using ObservableObject, if our model type is:

final class Person: ObservableObject {

@Published var name: String

@Published var age: Int

init(name: String, age: Int) {

self.name = name

self.age = age

}

}

We used to prefer doing this, splitting child views containing the smallest piece of data they need:

struct ContentView: View {

@StateObject

private var person = Person(name: "Tom", age: 12)

var body: some View {

NameView(name: person.name)

AgeView(age: person.age)

}

}

struct NameView: View {

let name: String

var body: some View {

Text(name)

}

}

struct AgeView: View {

let age: Int

var body: some View {

Text("\(age)")

}

}

In this way, when person.age changes, only ContentView and AgeView need to be refreshed.

However, after adopting @Observable:

@Observable final class Person {

var name: String

var age: Int

init(name: String, age: Int) {

self.name = name

self.age = age

}

}

It would be better to just pass person directly down to child views:

struct ContentView: View {

private var person = Person(name: "Tom", age: 12)

var body: some View {

PersonNameView(person: person)

PersonAgeView(person: person)

}

}

struct PersonNameView: View {

let person: Person

var body: some View {

Text(person.name)

}

}

struct PersonAgeView: View {

let person: Person

var body: some View {

Text("\(person.age)")

}

}

Issues

Beside lot of good things, we have kinda big problems as well with Observation framework

- No natural support for value types

Observation leads us to believe that structs are no longer appropriate for modeling domain types. If we want granular observation for these types and their nestings, then we should convert them to classes and apply the @Observablemacro

Which means that while using@Observable macro, we didn’t pay attention to the fact that we are now spreading reference types all over our applications. And it turns out that the @Observable macro simply does not work on structs. If you try to apply it to a struct you will instantly be greeted with a compiler error letting you know that the macro currently only works with classes.

But technically you can somehow skip that compile error if you will not use direct macro, and just copy/paste all the generated code into your model and then just swap class with struct.

struct HomeTask {

var title: String {

@storageRestrictions(initializes: _title)

init(initialValue) {

_title = initialValue

}

get {

access(keyPath: \.title)

return _title

}

set {

withMutation(keyPath: \.title) {

_title = newValue

}

}

}

var isCompleted: Bool {

@storageRestrictions(initializes: _isCompleted)

init(initialValue) {

_isCompleted = initialValue

}

get {

access(keyPath: \.isCompleted)

return _isCompleted

}

set {

withMutation(keyPath: \.isCompleted) {

_isCompleted = newValue

}

}

}

var priority: Int = 0 {

@storageRestrictions(initializes: _priority)

init(initialValue) {

_priority = initialValue

}

get {

access(keyPath: \.priority)

return _priority

}

set {

withMutation(keyPath: \.priority) {

_priority = newValue

}

}

}

init(title: String, isCompleted: Bool) {

self.title = title

self.isCompleted = isCompleted

}

@ObservationIgnored private let _$observationRegistrar = Observation.ObservationRegistrar()

@ObservationIgnored private var _title: String

@ObservationIgnored private var _isCompleted: Bool

@ObservationIgnored private var _priority: Int

internal nonisolated func access<Member>(

keyPath: KeyPath<HomeTask , Member>

) {

_$observationRegistrar.access(self, keyPath: keyPath)

}

internal nonisolated func withMutation<Member, MutationResult>(

keyPath: KeyPath<HomeTask , Member>,

_ mutation: () throws -> MutationResult

) rethrows -> MutationResult {

try _$observationRegistrar.withMutation(of: self, keyPath: keyPath, mutation)

}

}

extension HomeTask: Observation.Observable {

}

You can check that everything works absolutely same, as it was with reference types, so why does Apple engineers restrict us to use macro only on classes and not on value types ?

The behavior of observation for value types isn’t immediately clear. Value types, unlike reference types, are designed to be freely copied, with each copy being completely independent from the original. This raises several questions: Should copied values share the same observer registrar as the original? Or should each copy get its own separate registrar? Furthermore, if you copy a value, modify it, and then copy it back to the original, should their observer registrars be merged in some way?

var state: State = State()

var copy = state

This variables in Observation context will have lot of problems, cause the state and copy values are secretly sharing the same observation registrar, which contains a reference type deep inside, and therefore mutations made to the state are still going to notify anyone observing the copy value, which is kinda tricky.

This example demonstrates the challenges of applying the Observation framework to structs. Simply using the framework with structs doesn’t produce the desired results. One potential solution is to use copy-on-write semantics. When you apply the Observablemacro to a struct, it embeds a reference type within the struct. This allows the system to check if the reference type is uniquely referenced during mutations. If it isn’t, a copy of the reference type can be created to ensure correct behavior.

Philippe Hausler, the Apple engineer who initially proposed the Observation framework, developed a proof-of-concept for this copy-on-write mechanism. When a struct is mutated, it checks if the struct’s underlying Extent the reference type within the observation registrar is uniquely referenced. If not, it creates a new Extent.

However, it was eventually concluded that this approach wasn’t ideal. While creating a new Extent prevents mutations of the copy from notifying observations of the original state, it also stops observations of the copy itself. Since a new Extentis created, all of its internal state is reset, which undermines the purpose of observation in both the original and copied variables.

- Observation is only allowed in iOS17 and above

The deployment target required by Observation is iOS 17, which is a tough goal for most apps to reach in the short term. Consequently, developers face a significant dilemma: there are clearly superior and more efficient methods, but they can only be used two or three years from now. Every line of code written in the conventional way during this time will become future technical debt. It’s a rather frustrating situation.

Solution

Solution for backporting issues is perception library from PointFree guys

Swift-perception is library developed by two amazing engineers Brandon & Stephen

https://github.com/pointfreeco/swift-perception

The Perception library provides tools that mimic

@ObservableandwithObservationTrackingin Swift 5.9, but they are backported to work all the way back to iOS 13, macOS 10.15, tvOS 13 and watchOS 6. This means you can start taking advantage of Swift 5.9's observation tools today, even if you can't drop support for older Apple platforms. Using this library's tools works almost exactly as using the official tools, but with one small exception.

You can check their README for more information — using Perception is incredibly straightforward. It seamlessly integrates with TCA, and if you’re using iOS 17 or later, the framework automatically leverages the original Observation. For iOS versions below 17, it switches to Perception.

The team behind PointFree also provided a solution for Observation on value types. While it’s not a standalone package like Perception, their Composable Architecture includes a macro called [@ObservableState](http://twitter.com/ObservableState). This macro offers reliable and efficient observation for value types. Personally, I favor value types because they offer numerous advantages over classes. Most of the time, we only need value types. Even SwiftUI encourages the use of structs since views are now structs, unlike the days of UIKit when everything was a class. The [@ObservableState](http://twitter.com/ObservableState) macro ensures safe and effective observation for value types, which aligns perfectly with Swift’s emphasis on value types.

You can use TCA or check how they implemented ObservableState, cause verything is opensource.

I strongly recommend watching their video series on Observation, which covers the challenges, current state, and future of the framework. These videos professionally explain and test all the technical aspects, including solutions like ObservableState. It’s definitely worth investing in a subscription to PointFree, you’ll gain a lot of valuable insights and knowledge.

References

- WWDC23 Session — Discover Observation in SwiftUI

- Observation Documentation

- Source Code of Observation in Swift stdlib

- Perception — Observation from iOS13

- Observation The Future

Thanks for reading and happy hacking, in next episode of this article I will create Swift Observation Macro from Scratch, it will be kinda funny recreational programming session. 👾